Vittorio Storaro represents a transformative figure in cinema, marking a distinct “before” and “after.” Before Storaro, a cinematographer was often seen as just an executor, a technical role subordinate to the director, the film’s true creator. However, through his many collaborations, Storaro showcased to the Western film industry that light is first and foremost an expressive tool, a signature of the moving image; that lighting sets the emotional tone of a scene and can drive the narrative.

Storaro never favoured the title “director of photography,” seeing it as an Italian misinterpretation of cinematographer, the term used in the U.S. Throughout his career, he crafted a language that conveys the visual essence of an image, transcending mere storytelling.

From Rome to the Oscars: Storaro’s Illuminated Journey

Today, Vittorio Storaro, at 83 with three Oscars, stands as an international icon for on-set lighting. Born in Rome in 1940, he began studies at the Duca d’Aosta Technical Institute at 11 and later at the Experimental Cinematography Center. By 1961, he debuted with Franco Rossi‘s feature film Giovinezza Giovinezza his only black-and-white project. Storaro’s expertise truly shines in colour cinema, as colour remains his primary fascination in light management.

Storaro and Bertolucci: Light and Direction in Dialogue

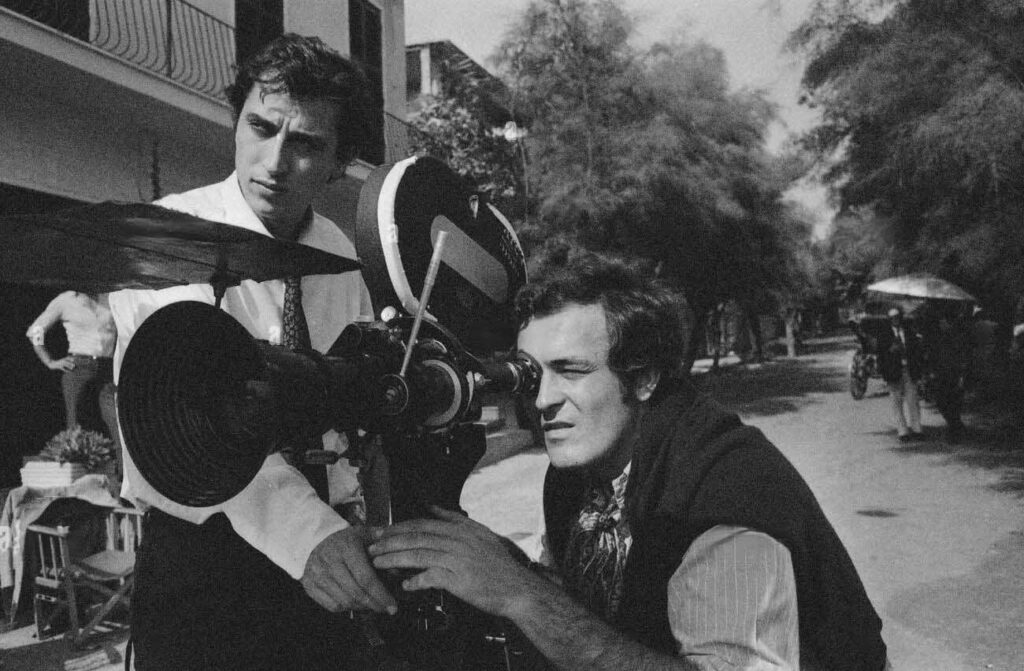

A defining moment in Vittorio Storaro’s career emerged from his partnership with Bernardo Bertolucci. They met young: Storaro was 23, Bertolucci 22. Their first film collaboration, La strategia del ragno, came in 1970. The film showcased early hints of Storaro’s style, using natural light to mirror the protagonist Athos Magnani’s disorientation during his journey through the Padanian countryside, tracing his anti-fascist father’s past.

However, the collaboration that left an indelible mark on both Storaro’s career and modern cinema was Il Conformista. A political drama set in the fascist era, this film was Storaro’s first true canvas to express his artistic vision. Set between Rome and Paris, it contrasts natural and artificial light, reflecting the tension between fascism and anti-fascism, indoors and outdoors: warm tones for the interiors and cold for the exteriors. But light also casts shadows, and it’s through manipulating these shadows that Storaro captures a visual tension echoing throughout art history.

Visual Masterpieces: Storaro’s Iconic Movies

Light, colour, and shadows: the three tools that this master of imagery wields like a maestro, enriching the visionary spirit of some of cinema’s greatest directors. His work with Francis Ford Coppola on Apocalypse Now is legendary.

In the film, the yellow of napalm symbolically portrays the violent push of civilization during the Vietnam War, set against the green of the jungle. This menacing, unknown, and boundless setting becomes the abyss for many American soldiers.

Similarly, Marlon Brando’s close-up as Colonel Kurtz, with shadows playing across his face, adds depth to his final monologue. Storaro also collaborated with Coppola on the 1981 film One from the Heart, where he freely channelled his visual inspirations into a vibrant romantic musical.

Beyond the Lens: Storaro’s Philosophical Imprint

Vittorio Storaro authored three books detailing his craft. Much of this stems from his theoretical exploration and ability to meld varied visual references with technical know-how from his early days. In Scrivere con la luce, he dives deep into his theories, gleaned from experience, effectively translating practice into theory.

What emerges is a view of light and colour as spiritual substances. Colours almost appear divine, being the intersection of light and darkness. When using light and colour in a communication medium like cinema, their symbolic significance is crucial, guiding the choice of shades for various scenarios.

Storaro’s significant contribution to cinema lies here: building knowledge from hands-on work while focusing on an element central to all art forms – light.