Cover photo: Kamilia Kard, A Rose by Any Other Name, 2021 installation view at Spazio Vitale, Verona 2024

Themes like identity, perception, hyperconnectivity, and the representation of bodies are at the core of Kamilia Kard’s artistic practice. The Italo-Hungarian creative builds images that engage with and expand reality—often through AI, which she describes as «a tool that facilitates the production process» while pushing expressive languages beyond the traditional limits of painting and sculpture.

Kamilia Kard will explore these topics in her talk Digital Architectures for Posthumans, part of Lumen, the event organized by Atmosfera Mag and A.A.G. Stucchi for Fuorisalone 2025. The event focuses on light and its intersections with artificial intelligence, design, and social interaction. The session is scheduled for April 10, from 6:00 PM to 7:00 PM. Registrations are now open.

How did you first approach non-traditional artistic media? What tools do you use to create art, and why did they attract you?

«It was a natural journey, driven by experimentation and curiosity for new languages. It’s a path that’s still evolving, and it encourages me to move across techniques—from the most traditional to the most digital and contemporary. If there’s one key element that shaped this transition, it is my desire to engage the viewer. That urge led me to experiment with interactive formats—websites, collaborative projects, AR filters, and virtual environments.

In net art pieces like Free Falling Bosch (2014) and My Love is So Religious (2015), visitors navigate scenarios and compositions with a single click. In Best Wall Cover (2012–2014), they contribute to building an online archive. In Loading Instructions (Mansplaining) (2021), they become part of the piece, playing a character within a video game.

Another reason I was drawn to new technologies is their sociological impact—their capacity to transform society and, in turn, art. For me, technical and theoretical research are deeply intertwined: my artistic practice raises questions, and theoretical study opens new possibilities».

What themes do you explore through your art? Where do you find inspiration?

«My work examines how hyperconnectivity and new forms of communication affect perception and the representation of the body, especially in how they shape emotional and affective experiences. I’ve always been drawn to human behavior—especially to its patterns of repetition, excess, and vulnerability.

The massive volume of content shared online—selfies, status updates, links, gaming sessions, moods—gives me a macro-level view of recurring patterns. I focus on the phenomena that emerge on the web, analyzing how they resonate with and influence everyday life».

If you had to name three works that best represent you, which would you choose—and why?

«Every work I’ve made has been essential to my research. They mark different stages in my journey, both personally and artistically. That said, I’ll highlight my three most recent projects: Toxic Garden (2022–2024), HERbarium Dancing for an AI (2023–ongoing), and A Love Story Like Many Others (2025–ongoing).

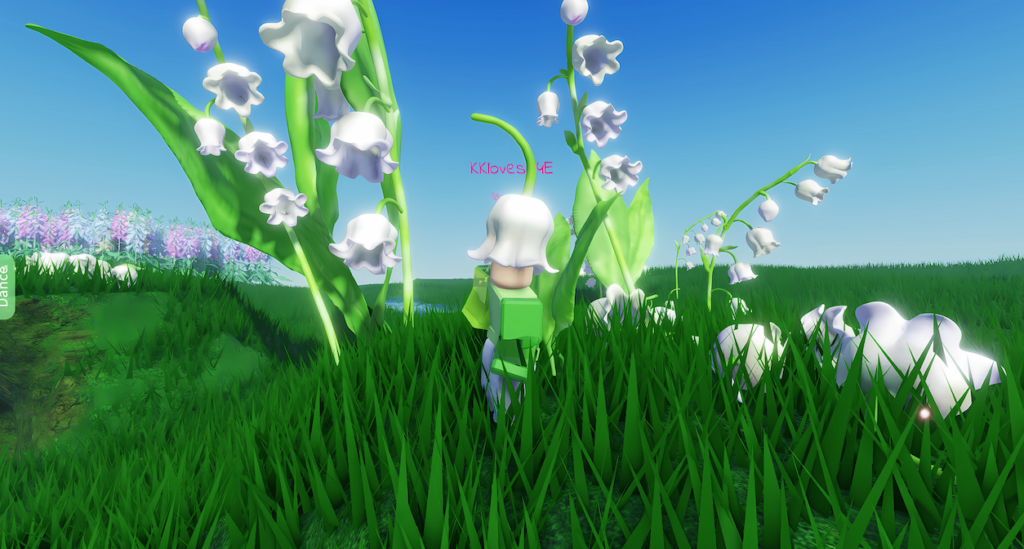

Toxic Garden is a participatory online experience hosted on Roblox, a popular metaverse among pre-teens and teens. It explores toxic behaviors in social and relational dynamics. The garden is a metaphor for digital space—seemingly welcoming and beautiful, yet full of hidden dangers and distorted narratives. Toxicity is central: just like some beautiful plants are poisonous, certain appealing behaviors can be harmful. I wanted to explore how digital communication amplifies these ambiguities, creating spaces where care and manipulation blur. In the world I created, users’ avatars lose their default identities and become hybrid plant-human beings—each one based on a poisonous plant.

The theme of poisonous plants, emotional dynamics, and interspecies relationships resurfaces in HERbarium Dancing for an AI. This performative work features anthropomorphic digital plants dancing with live performers in an interspecies choreography designed with the help of AI. I captured dance movements from three dancers on video, then fed the footage to the AI, which returned animations full of strange, unnatural errors. Instead of correcting these—as I did in Toxic Garden—I asked the dancers to learn the AI-generated choreography, interpreting even its awkward, artificial steps. In this piece, AI’s errors became a central choreographic and authorial element, driving both the digital plants and the human dancers. It’s a multi-layered interplay between human-machine, machine-human, human-plant, and plant-machine, where simulacra intertwine and influence one another, making it impossible to tell what came first.

As the name suggests, HERbarium also examines the role of women. The concept grew from the traditional image of women as witches and the recent sci-fi trope of AI as female. If women are witches, and AI is female, then AI is a witch. I imagined a techno-witch brewing love, death, and dream potions from digital plants and human bodies. The work has three chapters: Love Potion, Death Potion, and Dream Potion. I’m currently working on the final part, Psycho Potion.

Themes of womanhood, love, and online experience return in the sculpture series A Love Story Like Many Others. These 3D-printed busts of women interact with root structures—sometimes embracing them, others being pierced by them, always in the heart. The work focuses on romantic experiences shared online. While love stories often feel unique, they follow recognizable patterns—clichés amplified by social media through videos, screenshots, posts, and lipsyncs that invite collective recognition. When something hits the right note, it spreads. Users re-share, add captions, or reenact it, turning personal stories into collective narratives deeply embedded in our daily lives.

I sculpted multiple torsos to represent this repetition of the ‘same love story.’ The roots that wrap or bind them visually represent hashtags and keywords common in these digital tales—translated into metaphor. Each sculpture echoes experiences like love bombing or ghosting. While men also share similar stories, I chose to center on female voices and emotions. These sculptures are printed using a filament containing Egyptian blue, one of the first synthetic pigments in human history. Under X-rays, it fluoresces—giving these intimate, entangled female bodies a luminous, shared presence».

Do you use AI? What are its possibilities in the arts?

«Yes. As mentioned, I use AI both to support my creative process and as a subject of critical inquiry.

One example is A Rose by Any Other Name (2021), where I explore AI’s limits in recognition. I created an animated 3D model hosted on a website, imagining an AI unable to interpret hybrid forms—roses that move like fish, with skin-like textures tattooed with girly patterns, some reading “I’m a Daisy.” The combination of form, movement, material, and language creates perceptual confusion, making it hard for AI to categorize the object using its biased tags.

The title references Shakespeare’s famous line from Romeo and Juliet, suggesting that a name doesn’t change what something is—but in machine learning, classification is everything. On top of that, I added human-like behaviors to confuse the AI further: the roses kiss, embrace, and repeat affectionate gestures in a looped dance. Movement, emotion, interspecies hybridity, and AI speculation converge here».

How do you imagine, or hope, the future of art will look?

«We’re already seeing how art is evolving thanks to digital technologies—both in daily life and in creative processes—and through interdisciplinary collaborations. This shift isn’t just about how we experience art but how it’s made. Artists, engineers, scientists, and designers are working together to develop new expressive languages that push beyond traditional disciplines like painting and sculpture. These collaborations allow us to tackle complex themes—identity, perception, human-machine interaction—from fresh perspectives, creating works that reflect our hyperconnected, fluid society».