Cover photo: Digital scan, replic, and full-scale hologram of the Sarcophagus of the Spouses, a project curated by VisitLab Cineca, 2014

A trained humanist, Maria Chiara Liguori gravitated toward digital technologies. Today, AI, open-source software, and digital visualization are part of her daily toolkit. At Cineca, she works on cultural heritage projects powered by advanced computing.

Maria Chiara Liguori will explore these topics during the talk Digital Architectures for Posthuman Users, part of Lumen, the event by Atmosfera Mag and A.A.G. Stucchi held during Fuorisalone 2025, dedicated to light and its intersections with artificial intelligence, design, and social dynamics. The session will take place on April 10 from 6:00 PM to 7:00 PM. Le registrazioni sono ora aperte.

What is Cineca, and what do you work on there?

«Cineca is one of the world’s leading HPC centers, providing advanced digital solutions for academia, research, and public institutions. I work in the visualization lab, where we develop computer graphics for scientific research and cultural heritage projects. We’re currently exploring open-source AI tools to analyze and enrich cultural content.

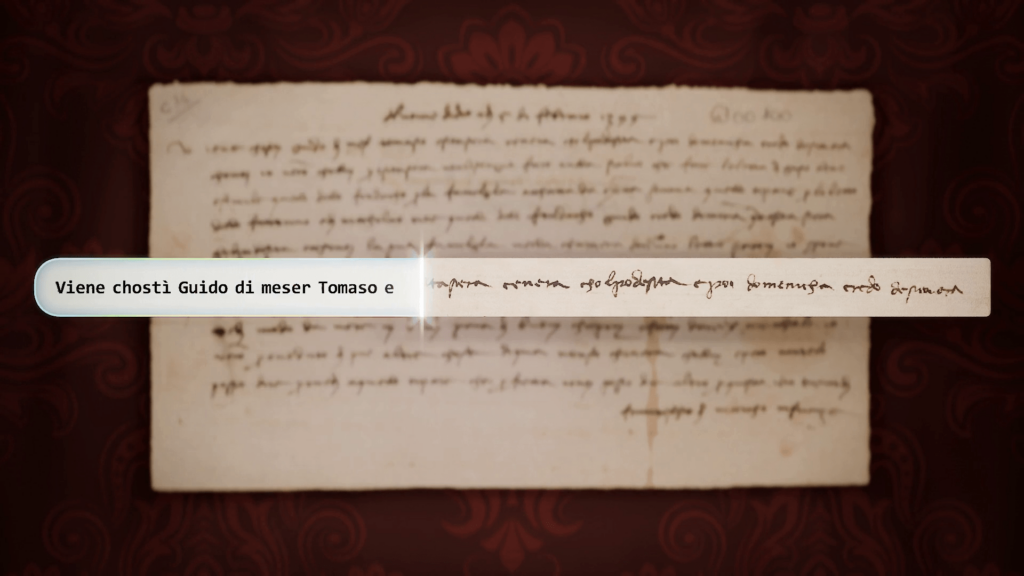

One project involves the automatic transcription of historical manuscripts, a massive body of letters and archival documents stored across Italy. Digitizing and transcribing them would streamline scholarly research, enabling keyword searches and thematic studies. Our case study is the letter collection of Isabella d’Este, mostly housed at the State Archive of Mantua and digitized by the IDEA project at the University of California, Irvine.»

What’s your professional background? How did you end up working in tech?

«I studied political science, then contemporary history. After visiting a museum of everyday life in the UK, I had the idea to create something similar—digitally—in Italy. In 2000, thanks to early grants, I developed the Virtual Museum of Everyday Life, with three domestic settings from the 1930s, 1950s, and 1980s.

I later earned a PhD in History and Computing, aiming to use technology as a tool for historical storytelling. My first contact with Cineca was during that museum project—we started collaborating, and eventually, I joined the team. At first, it was a mindset shift. Coming from the humanities, I had trouble understanding tech teams and vice versa. But over time, we learned to think together.»

How do the virtual and real coexist in museums? Beyond immersive reconstructions, what’s next?

«There’s huge potential, but collaboration is key. Tech developers need to understand the goals of curators, scholars, and museum professionals. Early on, we faced two extremes: some teams aimed for hyper-accurate reconstructions that felt dry to audiences, while others created dazzling visuals with no historical grounding. Today, we’ve found a balance.

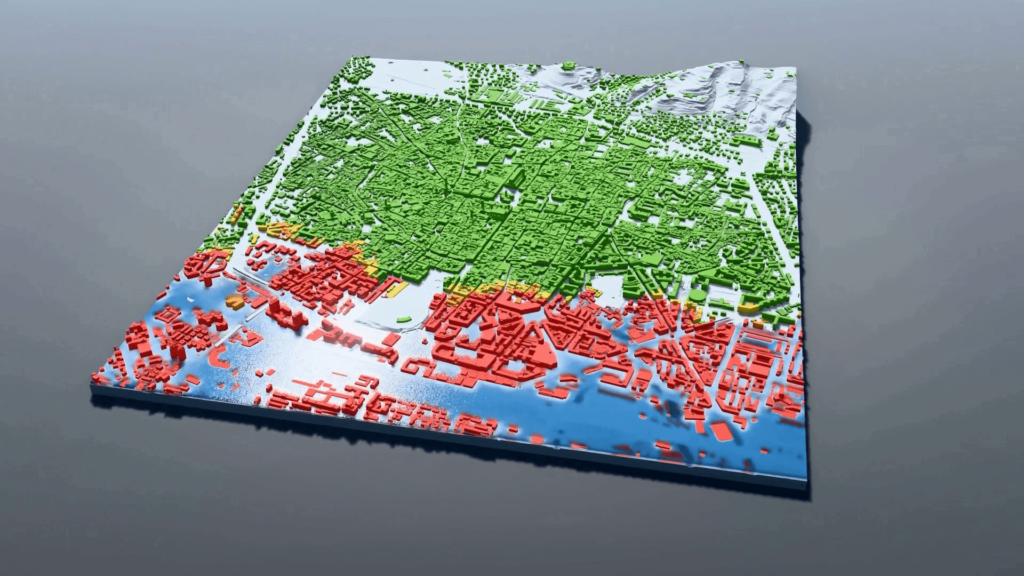

Take the project reconstructing Isabella d’Este’s studiolo. The space still exists, but its collection has been scattered across museums. We’re creating a virtual version and gradually reinserting the original artwork wich can evolve into a research database and, eventually, a navigable VR environment.

Another example is the Sarcophagus of the Spouses, an Etruscan terracotta masterpiece from the 6th century BCE. It’s too fragile to move from the National Etruscan Museum in Rome. In 2014, the Bruno Kessler Foundation captured it via photogrammetry while the CNR did a laser scan. Giugiaro made a replica for Bologna and later donated it to Cerveteri. Cineca created a full-scale hologram featured in a 3D mapping show during the Bologna exhibition. All from the same data set serving experts and the general public alike. The key is collaboration between developers and curators.»

What are the practical uses of AI in cultural heritage?

«AI often helps enhance image quality. Many manuscript microfilms from the 1950s and ’60s are too low-res for transcription software. AI can upscale them and make them legible. At Cineca, we also used AI to restore analog footage for a Rai documentary on Edoardo Bennato.

AI also supports 3D modeling, generating realistic materials and textures. Even without photos, AI can simulate surfaces with lifelike detail.»

What’s your view on AI-generated art?

«What matters is the artist’s intent. Not everything made with AI is art. The beauty of an image doesn’t define its value—what counts is the thought behind it.»