Bathed in the unease of chiaroscuro, with lights flickering on and off intermittently, Wong Kar-wai’s 2000 film, ‘In the Mood for Love’, uses (the absence of) lighting to tell an impossible love story. This masterpiece, contemporary with the Y2K bug and trends, transcends its time to craft a private aesthetic, reconstructing 1960s Hong Kong amidst rapid industrialization, Western aspirations, ringing phones, staircases, booths, offices, corridors, lamps, and streetlights. Spaces emit ‘light in the mood for love’ impulses like a booster for imagination.

The story unfolds a forbidden affection between a secretary and a journalist living in adjacent apartments, constrained within the Shanghai community in Hong Kong—a neighbourhood of capsule studios and one-bedroom apartments, where they love each other, literally, in the shadows. Both are married and morally upright. They suspect their spouses of having an affair, leading them to develop a strange friendship that evolves into an unexpressed surrogate couple.

This film, awarded at Cannes and universally acclaimed as a masterpiece, translates its uniqueness into the atmosphere, or as the title suggests, the mood. Wong Kar-wai’s genius lies in using visual art to narrate the story of Mrs. Chan and Chow Mo-wan through spaces, objects, lamps, and darkness. ‘In the Mood for Love’ returned to theatres in 2021 in a restored 4K version.

Light in Wong Kar-wai’s Cinema: hope, desire, and passion

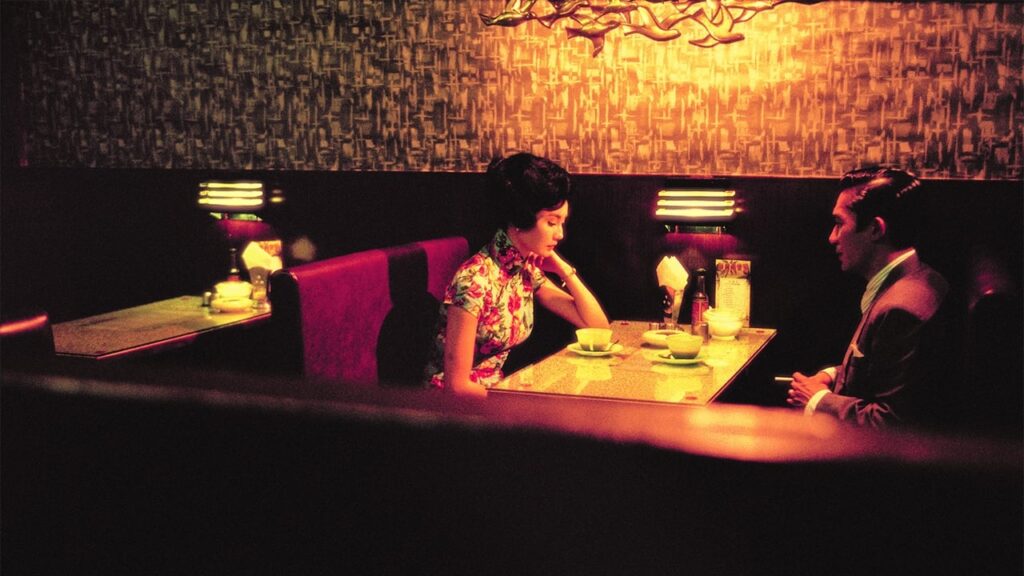

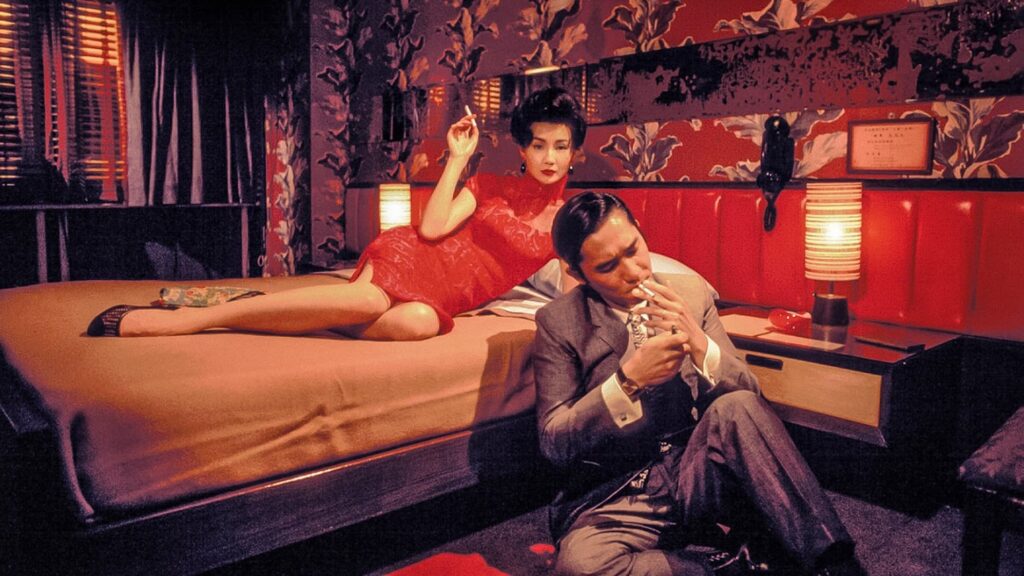

Light and shadow in “In the Mood for Love” are a film within the film. The protagonists, prey to repressed desires, find fulfilment in the gaps of lamps, streetlights, fragmented signs, and artificial lights, making the night a synthetic hallucination. Faces are lighted with anti-geometries: beams from below, above, and diagonally. The adjoining mini-apartments where Mrs. Chan and Chow Mo-wan live, immersed in cigarette smoke and noodle steam, are illuminated only by retro, yellowish 1960s lamps, blending Western and Eastern styles. Each frame of the film contributes to an aesthetic of nostalgia.

The choice of red and yellow as the primary scene colours, recurring in Mrs Chan’s cheongsam patterns and furnishings, represents the stifled passion and frustration permeating the environments. One evening we see them in a restaurant, illuminated by the precise light of a lamp that hangs over them like the sword of Damocles. A super-parties eye revealing everything: smoke clouds, trembling eyelashes, lips slightly parted that tonight too will not speak of love.

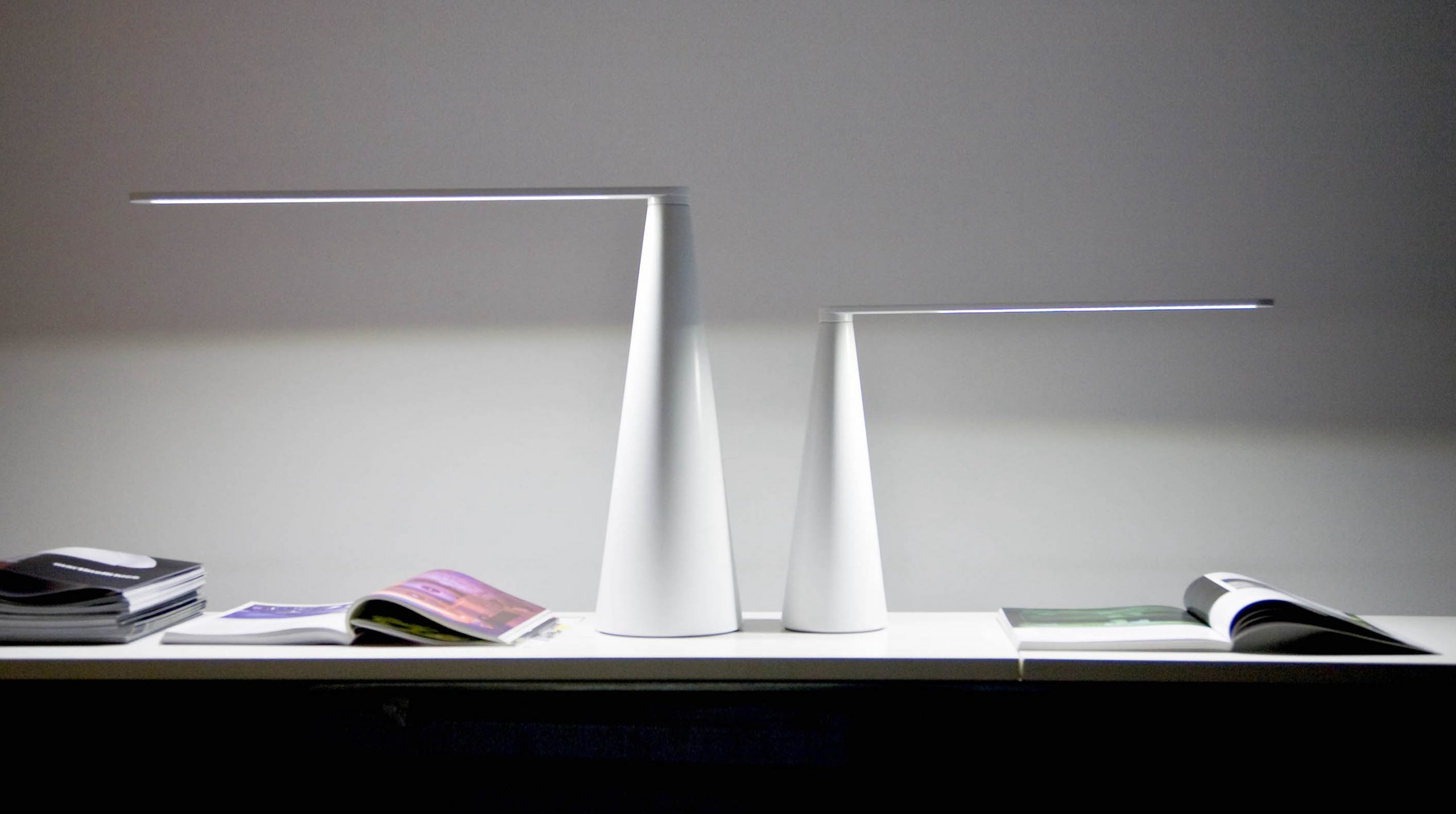

Wong Kar-wai entrusts these lamps’ light with the hope of unfulfilled desire. We need something more dazzling, but we will stay in the shadows.

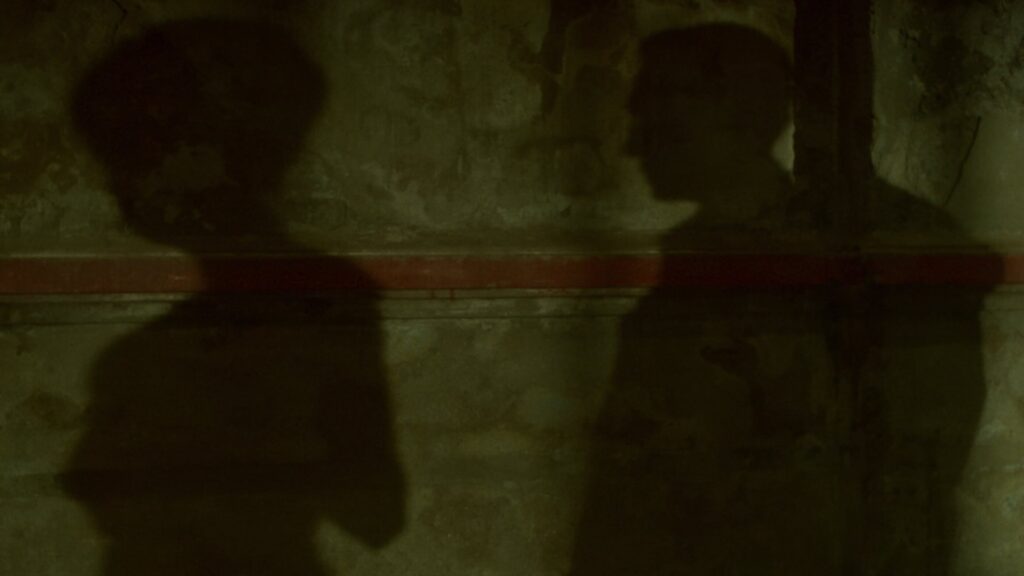

Shadows: From city alleys to the soul’s corners

Similarly, Wong Kar-wai leads us into a box of shadows as a state of mind, forcing us to squint to focus on what lies behind the darkness of alleys, long corridors, and corners. The long dark sequence showing the two going to the kiosk to get something to eat reveals their essence: that love is dark. And just like their shadows cast on the stairs of this sentimental noir. Shadow is a part of this film, broken into continuous tableaux.

The non-couple is a victim of the darkness of common sense, social conventions, and morals. Often spied upon through sharp edges assume the form of doors, mirrors, and windows, these imagined lovers invite us to discover an “absence”. Occasionally, the director introduces a small rustic lamp, but only to keep the possibility alive.

In the end, Wong Kar-wai sheds light on our discontent. Fantasies, like memories, evoke a diluted world that seems more beautiful than reality. But there is no clarity without darkness: life consists of reality and hopes, just as nostalgia for something never lived.