«Every era embraces the most advanced tools available—and redefines what artistic creation means through them», says Francesco D’Isa, highlighting how we have long used technologies that support and shape the act of making. Whether a paintbrush, a camera lens, or an AI model, they all play a co-authorial role in the final work. Generative intelligence needs time to feel ‘normal.’ A philosopher, artist, professor, and author, D’Isa is also the director of L’Indiscreto, a magazine that “explains difficult things simply,” a skill he embodies.

Francesco D’Isa will speak alongside Design Researcher Matteo Subet and Antonella Autuori in the talk Who’s Afraid of AI?, on April 10 at 7:00 PM, part of the Lumen Community Talks.

How did you approach AI and new technologies as a philosopher and artist?

«I came into AI quite naturally. I had already worked with digital media for years, and as a philosopher, I’d been interested in AI as a field of study from early on. As an artist, I started observing these tools in 2017 and used them frequently around 2020. So the current ‘boom’ is the next step in a path where theory and image-making have always coexisted. These new generative AIs perfectly combine language (i.e., words) with visual creation—two areas I have always cared about».

AI belongs to the present but projects us into a fast-approaching, unfamiliar future. Is this why it triggers fear?

«Fear tends to arise when something established feels threatened. Often, the strongest reactions come from established professionals or older generations who perceive a risk to the status quo. Every technological breakthrough is a ‘catastrophe’ in the original Greek sense—katastrophē, a radical upheaval.

Kirsten Drotner called this reaction media panic: a recurring fear that each new medium—from the printing press to AI—might endanger a society’s core values. The truth is, no one is ever fully prepared for a revolution like AI. But those who approach it with curiosity rather than fear have an advantage: they get to explore these tools with openness, turning them into opportunities for personal and professional growth».

When it comes to AI-generated art, the big question is: who is the author, the machine or the human?

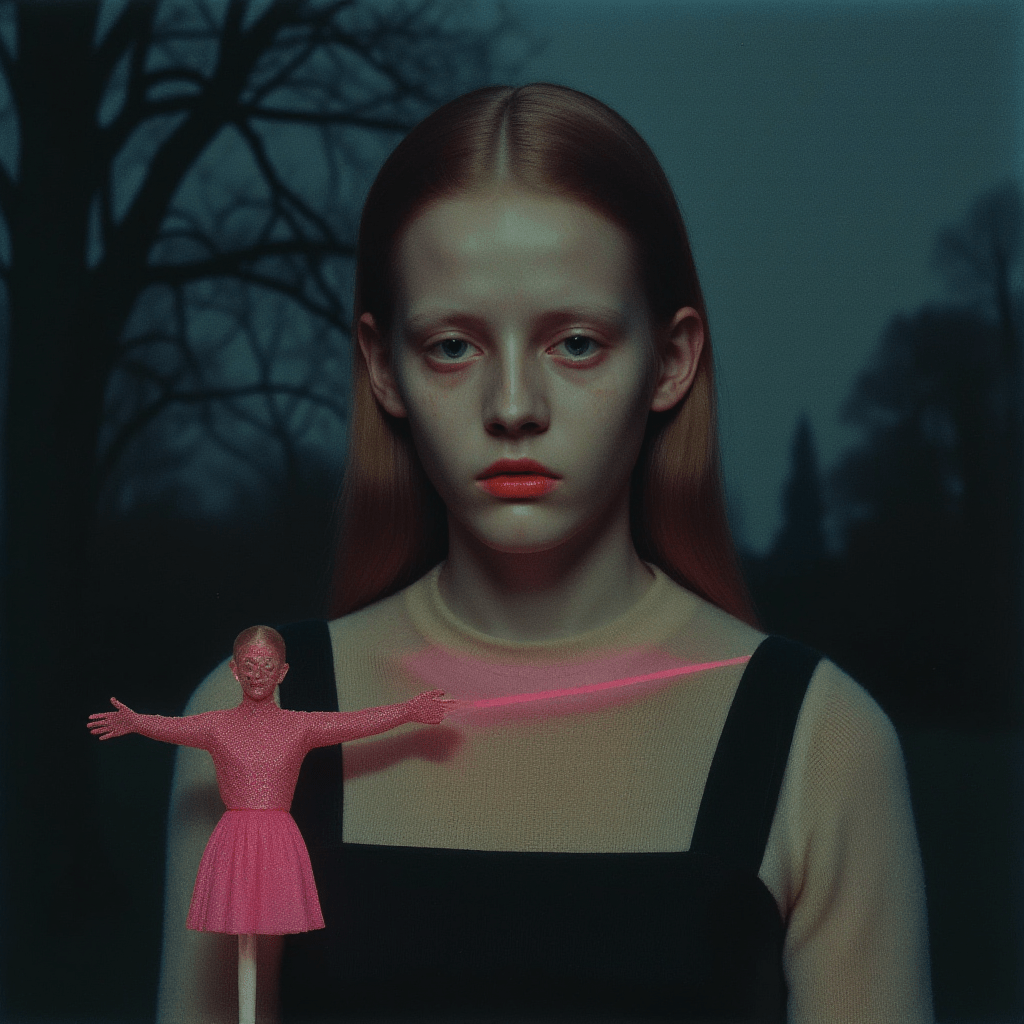

«Every creative tool we adopt comes with some level of co-authorship. Photography, for example, carries its own “program,” a mix of technical and cultural elements that influence the outcome beyond the photographer’s intention, as Vilém Flusser explains in Towards a Philosophy of Photography. We’re used to this silent collaboration. Brushes, lenses, and editing software have shaped our art-making for decades. Generative AI is no different. In text-image creation, the role of the artist does not disappear. It becomes more relational: you create the prompt, refine it, and engage in dialogue with the model. Words act as semantic attractors that steer the results. Then you select, rework, and compose outputs to develop a coherent visual style and meaning. Today’s tools go far beyond simple prompting. Artists have access to countless parameters. The machine offers unexpected suggestions, but the human shapes the story and gives it direction and emotional resonance. So the question isn’t: “Who’s the author, man or machine?” It’s about understanding that creation is always collaborative—rooted in complex networks of agency that aren’t always human or even contemporary. Co-authorship doesn’t diminish human creativity. We’ve long relied on tools that automate parts of the creative process. Now, we have one more».

We credit artists whose works are not handmade—Warhol’s prints, Hirst’s sharks, and cast-bronze sculptures based on sketches. Why does manual labor become sacred only when AI is involved?

«Manual skill hasn’t defined art for a long time. A critic once told me that someone like Bernini would be appalled by AI ‘replacing’ the artist’s hand. But Bernini used the most advanced tools of his time—and often delegated much of the work to skilled assistants under his direction. Every era, after all, adopts the most innovative tools existing and, with them, redefines the concept of artistic creation. What I love about art is that for every definition we create, there will always be a work that breaks it. That’s what gives art its fluid identity.

The term ‘artificial intelligence’ was coined in 1956 at the Dartmouth Workshop by scientists like McCarthy and Minsky. It was a lexical choice that shaped perception—it implies autonomy when AI is mostly just an algorithmic simulation of mental processes. Norbert Wiener’s earlier term ‘cybernetics’ may have better conveyed the idea of systems that govern or regulate without consciousness.

Some traditionalists—especially in the comics field—still cling to a “muscular” view of art, where manual effort and sacrifice are essential to authenticity. But art history shows us that while manual skill can produce wonders, it’s neither sufficient nor necessary for meaningful creation. What counts is the idea, the imagination, and the ability to orchestrate available tools—old or new—into something that speaks».