Ca’ d’Oro in Venice, gold scene, photo by Angela Colonna © courtesy of Studio Pasetti

For architect and lighting designer Alberto Pasetti Bombardella, light design is a complex field that intertwines scientific, perceptual, and cultural aspects. His design method focuses on the cognitive and physiological processes that define the relationship between space, materials, and human experience, where light becomes a narrative and emotional tool, particularly in museography.

Throughout your career, you have developed a design approach that places perception and the interaction between light, architecture, and experience at its core. How did this way of understanding lighting design come about?

«At first, my interest wasn’t directly in light but rather in museography—a highly delicate art of exhibition design that I had loved since my university years. My fascination was deeply influenced by Carlo Scarpa, whose poetic approach to design was evident in his works and in some of his followers, who were my professors at the University of Architecture in Venice. The transition from a passion for showcasing cultural heritage to a true cult of light was a natural one—because one cannot exist without the other. I realized early on, during my studies in California at the Getty Foundation, that research and scientific knowledge had to merge into a broad design vision to address the challenges of conservation and exhibition space design truly. The idea was to build on the legacy of the great masters who had shaped the history of exhibition design, both in Italy and abroad. My first step was studying the value of natural light to understand its implications for space, surfaces, and materials—creating an ideal balance between well-conceived architecture, exhibited works or artifacts, and light as the fundamental element connecting emotion and cultural curiosity. However, the Anglo-Saxon world had already moved beyond the physical-mechanical regulation of natural light—such as windows and skylights in art museums—in favor of a more stable artificial lighting system. By the early 1990s, lighting technologies had evolved significantly, offering new possibilities for illuminating objects and spaces, leading to extraordinary innovations that continue to this day. From that moment on, the challenge became exhibiting artworks according to the state of the art in technological advancements—disrupting outdated stylistic conventions and breaking free from the 19th-century exhibition traditions that still resisted extinction».

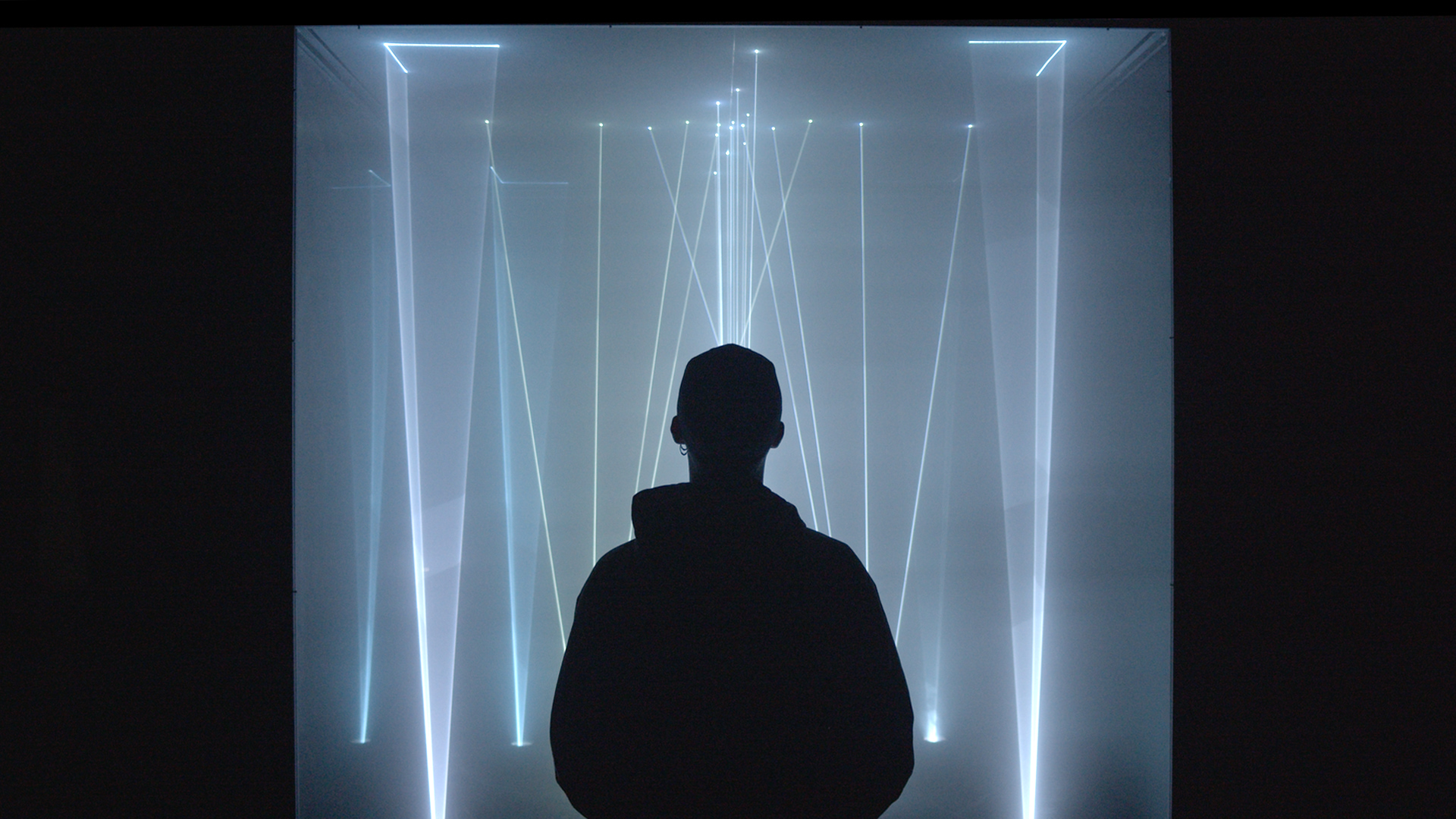

Each of us possesses a unique perceptual awareness that evolves and enriches our lives. A lighting project has the power to speak to this sensitivity, to make us part of a narrative, a story. This effect becomes even more pronounced—or at least different—when the project is dynamic. A perfect example is your work at Ca’ d’Oro in Venice or Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara.

«Yes. Dynamism is an incredible force in visual communication, but one must be cautious not to overuse it. Let me explain: a scene of contemplation comes from a meticulously orchestrated direction in the communication project. It is the culmination of multiple elements that must be carefully calibrated and harmonized. Many artworks from the 16th century were inherently tied to religious scenes or depictions of everyday life, where a diachronic effect was implicit. This is why artists often conceived events unfolding across different moments within a single composition. We could define this as implicit dynamism—a contrast to explicit dynamism, where static representation embeds a sequence of events within the artwork itself. When, however, the unfolding of events becomes a deliberate choice in the upgrading of a piece—so that the artwork or architecture acquires a mutable, evolving form—the stimulus is explicit, aiming to captivate the observer entirely by activating unexpected neural pathways. This is why understanding how our emotions function, synaptic connections form, and how physiological reactions are triggered through our perceptual system—shaped by a lifetime of experiences—is so fascinating. For instance, applying a dynamic narrative to a Cubist or Futurist artwork would make little sense, as movement is already inherent in the artistic concept. However, it can be incredibly stimulating when applied to a seemingly immobile work or structure. The façade of Ca’ d’Oro provided a unique opportunity to transform an implicit lack of dynamism into an expressive form, where movement—perceived through architectural layers, from the interior to the exterior—completely disrupted the two-dimensional concept of architectural perception at night. In this case, the inspiration came from the water rather than the stone. The perpetual, irregular motion of the water introduced a perceptual stimulus that places Venice in a state of continuous visual evolution.

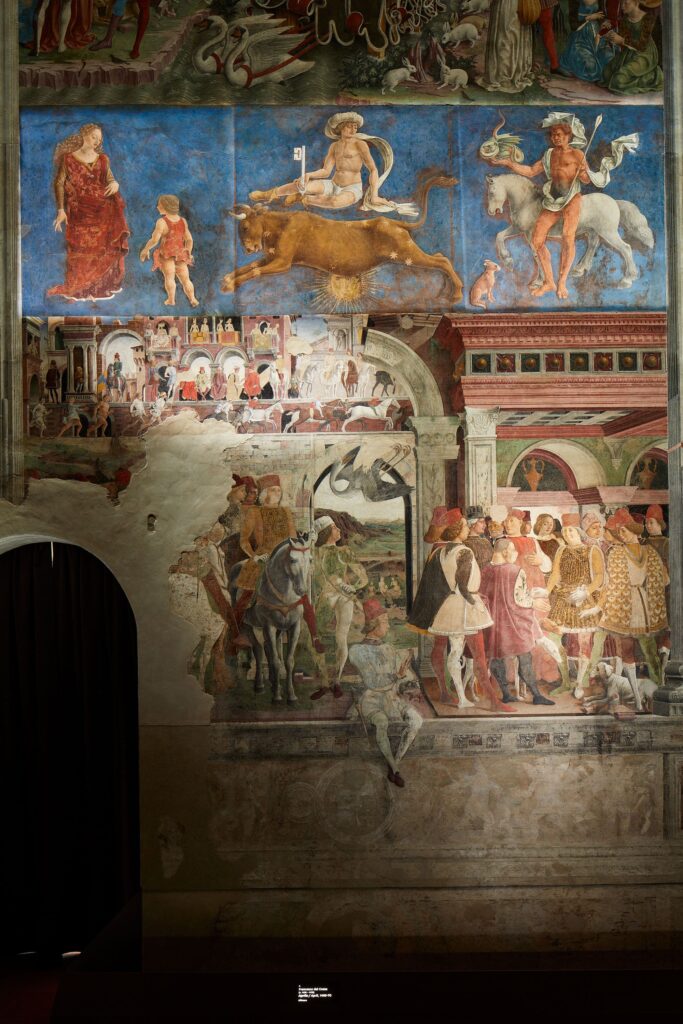

The Salone dei Mesi at Palazzo Schifanoia, on the other hand, presents an entirely different scenario. Here, the wall paintings—executed in both fresco and dry techniques—are illuminated by more than 50 different lighting scenes, enhancing details that are symbolically connected. In this case, the mind wanders freely among the various forms of apparitions, uncovering the most unexpected aspects of an artistic masterpiece unlike any other—a world where divinities, astrology, and scenes of daily earthly life intertwine».

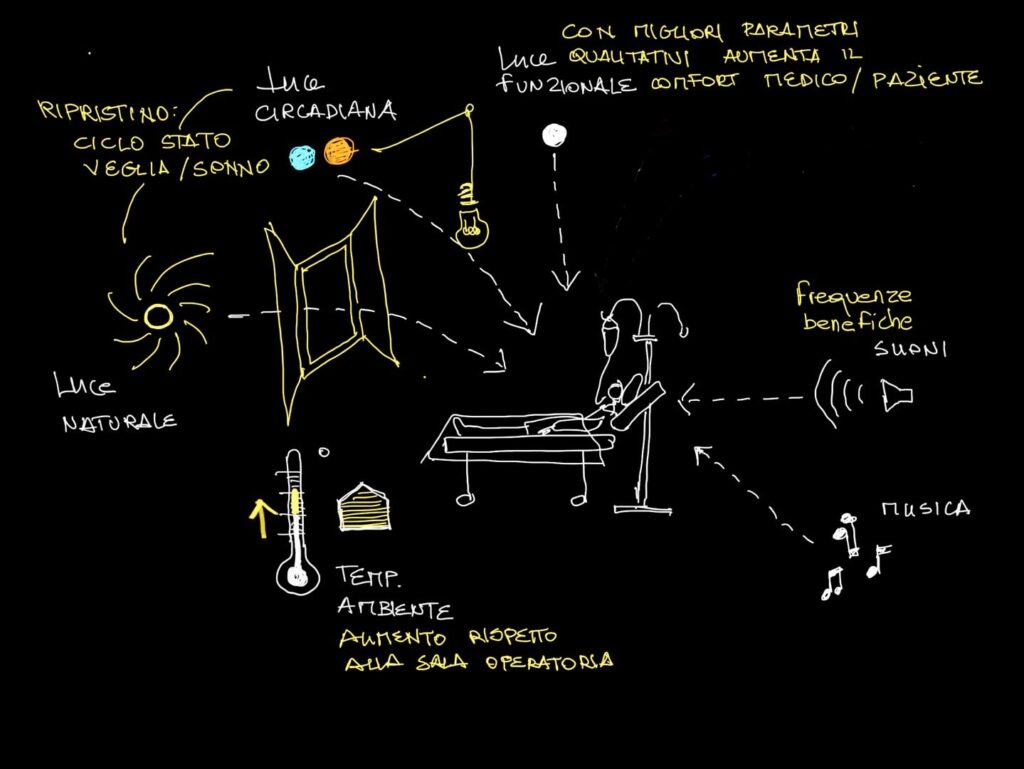

Your perspective applies well to the enhancement of cultural heritage. Neuroscience research offers new possibilities, particularly in areas where light is directly linked to human well-being. How can lighting design contribute to creating healthy and ergonomic environments that address not only individuals’ visual needs but also their biological and emotional well-being?

«For years, I have learned to distinguish between lighting engineering, lighting design, and quantum physics. The latter has led researchers toward a holistic vision of energy—one that embraces magnetic fields and their interaction with the surrounding environment. On the other hand, what we referred to as lighting engineering twenty years ago has gradually been enriched by a more advanced and conscious approach to lighting design, as some practitioners understand it today. This is a multidisciplinary field where various specializations and areas of expertise converge—not solely based on technical knowledge, calculations, or compliance with regulations. For me, the role of conscious lighting design has moved beyond conventional classifications. Let me give an example: in the context of an art museum, lighting considerations must inevitably include preservation requirements for the collections. At the same time, there is a need to enhance the exhibition content while ensuring functionality for visitor navigation and safety. Particular attention must be given to the architecture, the spatial environment, and the relationship between the museum’s interior and exterior. What is not always acknowledged in collective consciousness is that each directly impacts perception physiology and, consequently, the psychophysical well-being of those who experience a given space. The leap from a museum to a home or a healthcare facility is a small one when we consider how light, across different contexts, can activate profound responses in both our brain and body. Even the contemplation of beauty—whether in art, architecture, or a natural landscape—can generate states of well-being. The release of endorphins and oxytocin can trigger an immediate psychophysical reaction, but also what I call a “slow-release” benefit that lingers in both the body and mind. Light, when administered in the right dosage and with specific qualities, becomes a carrier of metabolic vitality and a continuous stimulus for therapeutic and calming effects.»

Many designers today still design exclusively for the sense of sight, focusing solely on creating something visually appealing (…) One thing I learned from Japan is precisely this design approach that must consider all the senses,” said Bruno Munari. Do you think this observation also applies to lighting design?

«Over the years, I have realized that the world of light is much broader than what is typically covered in artificial or natural illumination fields. At university, we were taught how to calculate illuminance using tables, paper, and pen, based on the sun’s radiation. Earlier, in school, we learned how photosynthesis works. However, when it came to understanding its effects on humans, the approach was purely theoretical and entirely insufficient. I remember two fundamental figures that greatly impressed me and shaped my desire to understand what happens cerebrally and physiologically when exposed to specific stimuli. One was the artist James Turrell, who shifted his focus from visual and sensory art to exploring the celestial vault and its effects on humans in his extraordinary Roden Crater project in Arizona. The other was neurobiologist Semir Zeki, a pioneer of Neuroaesthetics, who unlocked a deeper understanding of the visual cortex in connection to emotions, the symbolic interpretation of images, and how the brain perceives them. Both approached their work from a dual perspective—part humanistic, part scientific.

In this sense, Munari had already grasped that a design can only function at the highest level with a deep understanding of the senses. Certain stimuli activate the neural connections that form the foundation of emotion and the psychophysical intensity of an immersive experience. The inauguration of the Capitular Hall at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco was an experience conceived along these lines. The progressive illumination of Tintoretto’s large canvases, starting from the altar, revealed them in pairs (one on each side of the hall). Simultaneously, for each painting, two singers below would begin to sing, gradually surrounding the audience in an aulic chant. This interplay of light and sound heightened the perception of the frescoes, making the colors and figures even more vivid in a true synesthetic experience.»