Light in cinema is proof of how this ancient machine intertwines dreams and reality. It is an art that transcends space and time, restoring depth and three-dimensionality to stories. Cinematography ignites magic, creates atmosphere. It shapes space and defines the stylistic register. Lighting designers and cinematographers are the artisans of the invisible: together with the director, they work on the mechanisms of perception, adjusting or remodulating light and shadow.

There are films we remember—and will continue to remember—precisely because of their light. Because of stylistic choices, contrasts, or a chromatic palette so powerful that it enshrines those titles in cinematic mythology. Directors like Ridley Scott, Stanley Kubrick, Wong Kar-wai are not just storytellers but demiurges of worlds—defining, illuminating, and coloring them. The films selected here tell stories within stories, narratives of cinematographic photography. Which films are they, and why are they considered so significant?

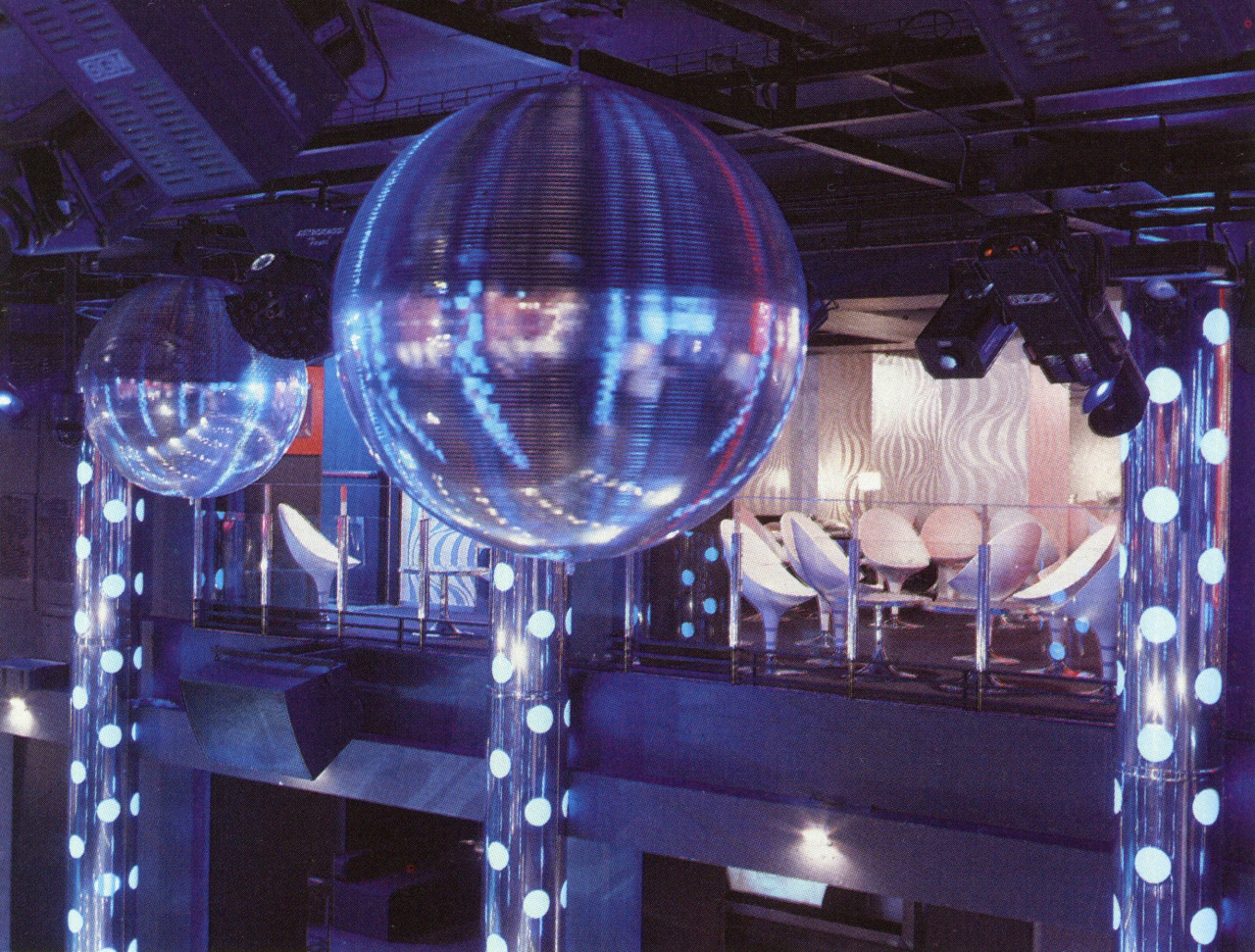

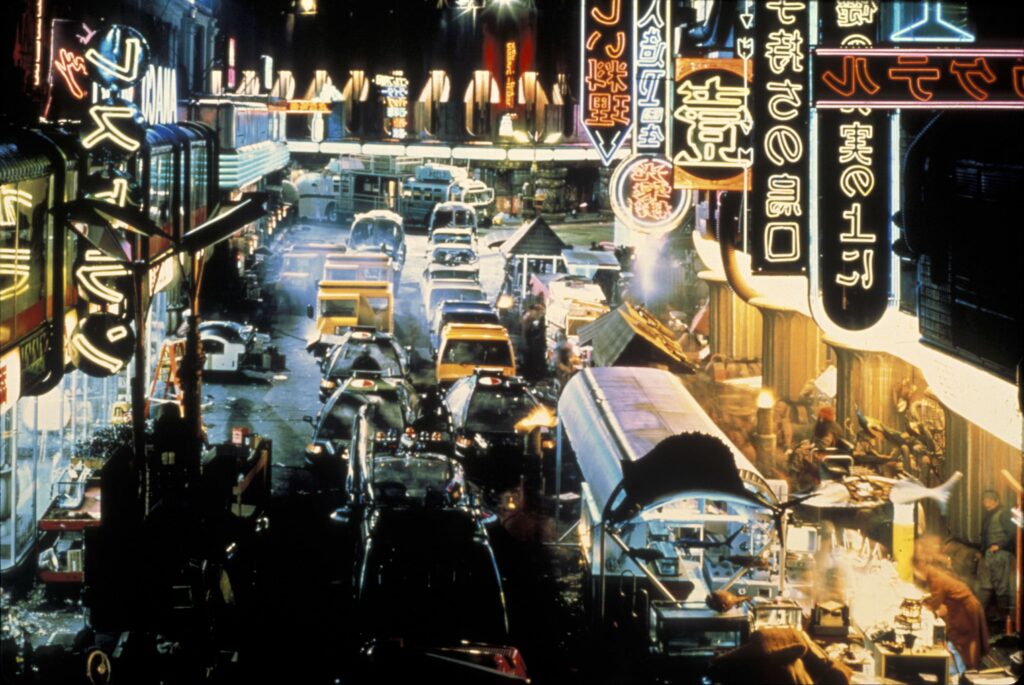

Psychedelic lighting in “Blade Runner”

Ridley Scott and cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth shaped their cyberpunk dystopia with a mix & match of lights: soft blue glows, icy and sharp beams, flickering flashes, and backlighting that turns characters into silhouettes against a sci-fi universe.

The use of neon, often in shades of blue, purple, and green, becomes the symbol of technological overcrowding: Los Angeles is an early Black Mirror, dominated by holographic advertisements, flashing signs, and neon inscriptions.

Light is often fragmented through wet surfaces, glass, and mist, creating a sense of alienation, reflecting humanity’s struggle against progress.

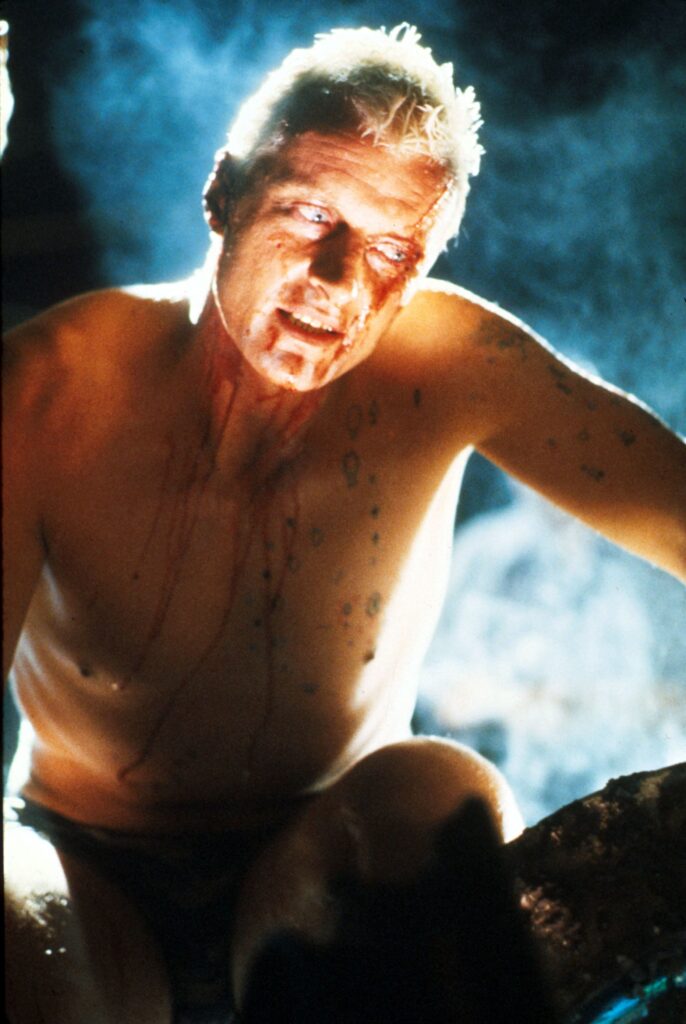

Natural light in “The Revenant”

The Revenant by Alejandro González Iñárritu is unique: Mexican cinematographer Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, nominated for an Oscar for his work on this film—as well as on Gravity and Birdman—used only natural light, aided by the choice of digital cameras.

The incredible story of Hugh Glass, who survives a bear attack and several days in extreme conditions along the Missouri wilderness, had to be told with a neorealist approach. “We wanted to give the audience a strong, visceral, immersive, and naturalistic experience. […] Make them feel as if everything was happening right in front of their eyes. We wanted them to feel the biting cold, to see the actors’ violet lips and their breath on the lens, to experience the powerful emotions of the story,” Lubezki told Codex.

Candlelight in “Barry Lyndon”

The great beauty of Stanley Kubrick’s period drama could inspire the provocation of watching the film with the sound off, to fully immerse oneself in Kubrick’s perfect tableaux, the pastoral atmosphere, and the natural light compositions. The added value comes from candlelight, illuminating the 18th-century aristocratic salons.

The golden glow of candelabras, captured by Kubrick and his trusted cinematographer John Alcott, gives an unprecedented realism to the noble faces, accentuating expressions and avoiding that artificial, commercial look often found in period films.

Visionary light in “Metropolis”

A manifesto of Expressionism, Metropolis by Fritz Lang—a 1927 silent film, shot in black and white—chooses contrast as its key element, dragging viewers into a revolutionary visionary experience.

The power of distortion, exaggeration, and light pushed to extremes—only to plunge suddenly into darkness—defines Metropolis and the artistic movement that developed in Germany in the early 20th century.

Metropolis tells the story of class struggle through light: the hyper-illuminated mise-en-scène clashes with the shadows cast by the characters, a visual device representing the war between the working class and the capitalist system. Through a population of allegories and a rich visual storytelling, Metropolis conveys anxiety, fear, and horror, stretching and compressing light and shadows, manipulating blinding sources and pushing darkness to its limits.

Theatrical light in “La La Land”

Cinema is the mirror of illusions. In La La Land, Damien Chazelle tells a love story destined to last only in the imagination, because reality is too prosaic and compromised.

Light supports this dreamlike universe, linked to the musical genre. Through cinema, one can step into a colorful, idyllic interlude, detached from the banality of real life. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren borrowed super-saturated colors, directional spotlights, and light transitions from classic musicals like Singin’ in the Rain and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

The symbolism is built on warm golden and orange lights for romantic moments and cold blue tones for misunderstandings and separation. Also noticeable are the scenes lit by theatrical spotlights, a single beam of light directed at the characters, emphasizing the film’s meta-theatrical nature: Is this a musical, a dream, or real life?

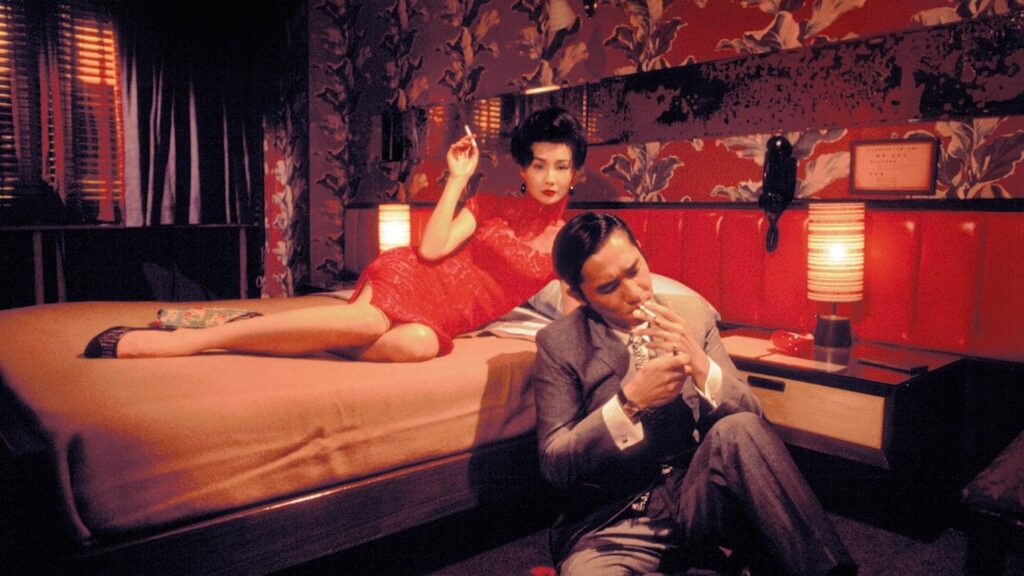

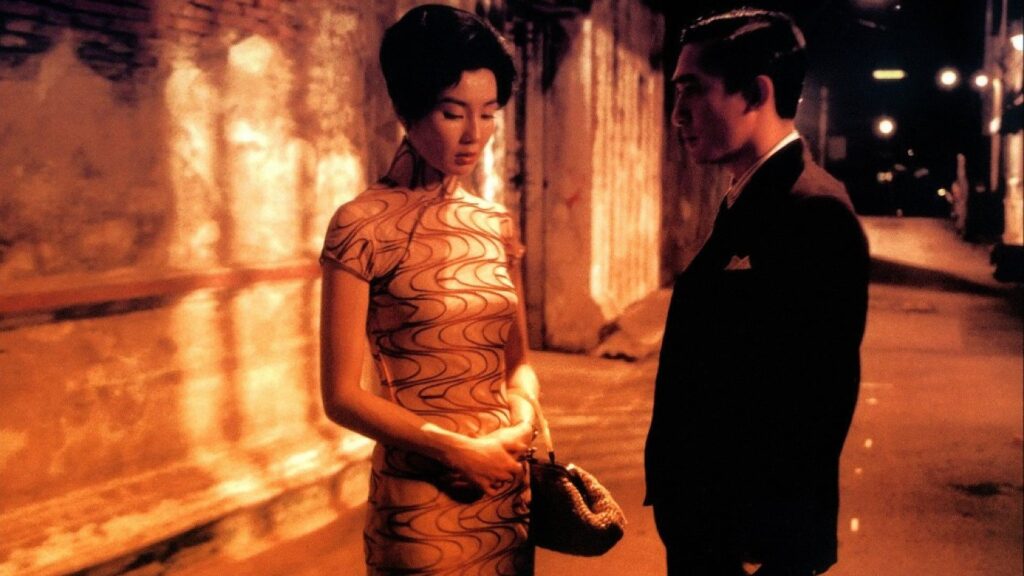

Emotion through light in “In the Mood for Love”

The aesthetic of Wong Kar-wai’s masterpiece is one of the best arguments for cinema as a gateway to dreams and salvation.

In In the Mood for Love, frames are composed like constellations of warm orange lamps, nestled in dimly lit spaces to convey depth and unspoken desire. The cinematography, handled by multiple cinematographers in succession, recreates a Hong Kong suffocated by minimal spaces, using a palette of amber tones, deep greens, and melancholic blues.

A non-love story unfolds in a dark cocoon, occasionally interrupted by a flickering lamp or a distant streetlight. Shadows and highlights are meticulously orchestrated, crafting a portrait of languid melancholy.

How light shapes Cinema

Great directors seize every opportunity to use light to shape their microcosms. Whether it’s psychedelic cinematography (Blade Runner), extreme contrasts (Metropolis), geometric compositions imbued with sentiment (In the Mood for Love), or naturalistic realism (Barry Lyndon and The Revenant), light is a narrative amplifier—enhancing symbolism, emotion, and conflict.

It is through the ability to innovate, particularly in cinematographic lighting, that filmmakers find the key to making cinema an immortal art form.